Category Archives: Architecture

Horticultural history in full bloom

Last week the long-list for this year’s Samuel Johnson Prize (Britain’s “most important” prize for non-fiction) was announced, and I just happen to be reading one of the nominees at the moment — A Thing in Disguise: The Visionary Life of Joseph Paxton by Kate Colquhoun.

Sir Joseph Paxton (1803-1865) was the 6th Duke of Devonshire’s gardener, and he became famous as the architect of the Crystal Palace, home to Britain’s first international exhibition of industrial accomplishment, The Great Exhibition of 1851.

Initially Paxton worked for the Duke of Devonshire at Chiswick House, which is approximately a mile from where we live in west London. According to English Heritage, which now manages the property, “Chiswick House is the first and finest 18th century Palladian villa in the country”. It was built in 1728, and was essentially the Duke’s country house closest to London.

Not much appears to be known about Paxton’s early career at Chiswick, but having read about its garden and greenhouse in his biography, Sudsy Dame and I walked over on Sunday to have a look. According to Colquhoun:

When the 5th Duke of Devonshire inherited the house, he commissioned Wyatt to add two substantial wings to the building and, in 1813, the 6th Duke, wealthy enough to indulge his passion for building and for horticulture, gilded the velvet-hung staterooms and commissioned Lewis Kennedy to create a formal Italian garden. Samuel Ware — later the architect of the Burlington Arcade — built a 300-foot long conservatory in the formal garden, backed by a brick wall, with a central glass and wood dome. In time, it would be filled with the recently introduced camellias which, along with the exotic animals, captured the very height of Regency fashion.

In a subsequent footnote, Colquhoun writes:

The Italian garden, the conservatory and many of the original camellia plants still exist at Chiswick House Gardens, London, W4. The first book on the subject of the camellia appeared in 1819, Monograph on the genus Camellia by Samuel Curtis, and listed 29 varieties being grown in England.

Well as you can see, the camellias are still blooming. It is amazing to think that these shrubs have grown here for almost two hundred years, but we saw one label stating 1823 and another citing 1795. Despite the genteel decay that now pervades Chiswick House and its garden, the flowers remain magnificent. It’s yet another example of how history is positively tangible in this crowded, over-developed part of the world.

Some Very Local History

“You have to give this much to the Luftwaffe: when it knocked down our buildings it did not replace them with anything more offensive than rubble. We did that.”

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, 2 December 1987

Earlier this week in the local studies section of my public library I found this photograph taken in 1905 of the street in which I currently live. Note the complete absence of automobiles and the tall chimney at the end of the road, part of an engine house that was destroyed in the 1970s. I live on the right hand side of the street, about half way up towards the chimney.

Some months ago just out of curiosity I searched for the street on Google, and I found a memoir written by Elizabeth Anne Slusser née Burbury (1915-1991), who lived in the house next door to mine from 1915 to 1939. Elizabeth Slusser appears to have had an interesting life. She was born in London to a wealthy and well connected family. In her memoir she describes annual holidays to Brittany and the year she spent learning Italian in a Catholic convent in Florence when she was just seven. She describes her home in London a little, and mentions her subsequently famous neighbours several times (Dame Marie Rambert and her husband, the theatre impresario Ashley Dukes, lived just across the street).

[Elizabeth’s parents met in Tasmania, but moved to England soon after marrying. Once settled in London her mother, Daisy Burbury née Guesdon, “founded a literary salon at 32 Campden Hill, Notting Hill Gate, which was frequently visited by Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, Maurice Baring and others. There is a statue of her in the House of Commons as the Virgin Mary, with her daughter Norah as the infant Jesus.”]

Elizabeth’s memoir comes to an abrupt end in August 1939, but not before she mentions that her family’s home was one of the first in London to be destroyed by a German bomb in 1940. I can vouch for this fact because I now live next door to the four new homes that were subsequently built on the bombed site in 1955/56.

These four homes are all contained in what must be the single most ugly building on the street. In typical post-war fashion, the developers allowed function to completely overwhelm form, but then they compromised the functionality by squeezing far too many features into the limited available space. Each of the four houses was provided with a small covered car port, which cannibalised a significant portion of the ground floor and yet can only be used for the smallest of contemporary automobiles. In an effort to save costs, cheap and ugly materials were used to construct the building. Even the window boxes, which can probably withstand an earthquake, are made of cement and permanently affixed to the exterior walls with steel rods. What was the architect thinking?

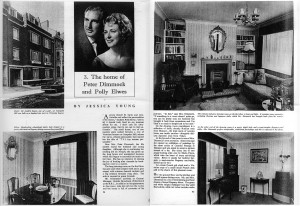

Imagine my surprise then when during my visit to the library, I also discovered a 1962 article from Homes and Gardens magazine featuring the house next door. Apparently, it was the home of two television celebrities, Peter Dimmock and his wife Polly Elwes. He was a presenter on the BBC’s flagship sports programme Sportsview, while his wife presented a current affairs programme called Tonight.

As you can see from the accompanying image (caution, it’s a long download at 644Kb), the article was illustrated with several images which give you a good idea of how it was furnished and a sense of what it must have been like to live there in the early 1960s. Ironically, Mrs. Dimmock is quoted as saying:

“A home should be warm and comfortable and reflect the personalities of its owners; above all it should look lived in – no museum effects for me. I don’t care for ultra-modern styles, they’re too apt to feel unfriendly.”

Well that might all be true, but did you look at the place from across the street before you moved in? Warm and comfortable? I don’t think so. More like sterile and frightening.

I don’t know when Mr. and Mrs. Dimmock moved out, but the house was sold late last year and in February workmen began to knock down all the internal walls and rebuild the insides from scratch. I wonder if the finished home will be “warm and comfortable” or more in keeping with its “ultra-modern” exterior?

I can’t wait for the new owner to move in next month, so I can recommend the local library.